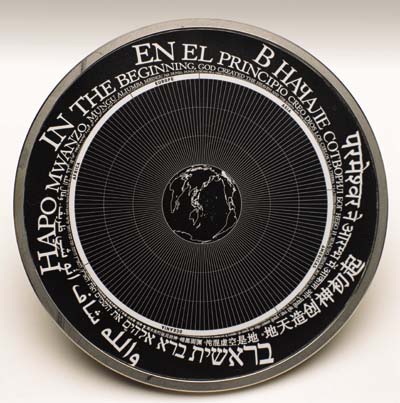

The Long Now Foundation has produced a Rosetta disk containing 13,000 pages of information regarding 1,500 human languages. The text is engraved, not encoded. The text starts out large enough to read with the naked eye and becomes continuously smaller, strongly suggesting one should examine the disk under magnification to read further.

Long Now is trying to preserve documentation for thousands of years, but I just want to know how to preserve documents even for a few months or years. They want to hold on to knowledge as civilizations come and go. I’m just trying to hold on to knowledge as personnel come and go.

Mundane document preservation is a very difficult problem. Preserving the Declaration of Independence is easy; preserving meeting notes is hard. Preserving the Declaration is a technical problem. If you keep it in a glass case filled with nitrogen, keep the lights low, and make sure Nicolas Cage doesn’t steal it, you’re OK. Millions of people know that the document exists, and they know where to look for it. And besides the original paper copy, the text is available electronically in countless locations.

How do I preserve the document that describes why my internal software application uses the parameters it does? Make notes in the source code? Good idea, but most of the people who want to know about the parameters are not software developers. What about version control systems or content management systems? Great idea: put everything associated with a project in one place. But wherever you put the information, someone has to remember that it exists and know where to look for it.

Pingback: How to preserve documents — The Endeavour

I like that idea… for now, the best I found is to keep /all/ in /one/ place: google docs… hoping that this service stays alive for some time… and thinking about how to make backups in an efficient way…

Trying to browse the Rosetta disc on-line made me aware that the problem (at least in out short-term version) is not that much to simply /preserve/ data, but also to /find/ what you are looking for in your archive. While I don’t /loose/ my documents, I’m unable to /find/ a given one – unless it’s in a more or less well structured archive which is “universally” accessible (from home, office, and on travel…) and can contain “everything”.

Back to the Rosetta disc, I was even unable to find a text in a given language (say, German). Actually, I even did not succeed in location the sector “Europe”. (Hoping for alphabetical order, after “Africa” and “Asia” I ran into “Oceania”… ?)

I suppose the Rosetta disk is optimized for a different kind of search. They want to maximize the chances of someone being able to understand the purpose of the disk, not the maximize the speed at which someone in our time can find things. Finding this disk in the future might be something like discovering the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947, a discovery that took decades to process.

You say “Preserving the Declaration of Independence is easy; preserving meeting notes is hard”. Surely the problem is preserving the media not the actual information. Even with nitrogen and low lights the document will eventually degrade though it might take thousands of years. On the other hand your photograph of the Rosetta disk will probably be archived many times somewhere on the internet and may even exist at the end of history. I have fossil stromatolites from the period of the first unicelluar life on earth 2 billion years ago. “Information” can exist easily that long but the problem is that we have almost no power to select what will remain and what will be lost – even if it is the Rosetta Stone or the Declaration of Independence.