Patrick Vandewalle, Jelena Kovačević, and Martin Vetterli have published a new article “Reproducible Research in Signal Processing: What, Why, and How” in IEEE Signal Processing Magazine (37) May 2009.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Preserving (the memory of) documents

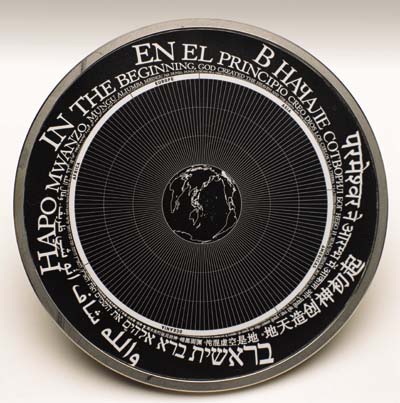

The Long Now Foundation has produced a Rosetta disk containing 13,000 pages of information regarding 1,500 human languages. The text is engraved, not encoded. The text starts out large enough to read with the naked eye and becomes continuously smaller, strongly suggesting one should examine the disk under magnification to read further.

Long Now is trying to preserve documentation for thousands of years, but I just want to know how to preserve documents even for a few months or years. They want to hold on to knowledge as civilizations come and go. I’m just trying to hold on to knowledge as personnel come and go.

Mundane document preservation is a very difficult problem. Preserving the Declaration of Independence is easy; preserving meeting notes is hard. Preserving the Declaration is a technical problem. If you keep it in a glass case filled with nitrogen, keep the lights low, and make sure Nicolas Cage doesn’t steal it, you’re OK. Millions of people know that the document exists, and they know where to look for it. And besides the original paper copy, the text is available electronically in countless locations.

How do I preserve the document that describes why my internal software application uses the parameters it does? Make notes in the source code? Good idea, but most of the people who want to know about the parameters are not software developers. What about version control systems or content management systems? Great idea: put everything associated with a project in one place. But wherever you put the information, someone has to remember that it exists and know where to look for it.

Legal frameworks

Greg Wilson has a new blog post Legal Frameworks for Reproducible Research.

Orfeo Toolbox

The Orfeo Toolbox is an open source library of image processing algorithms developed by the French Space Agency (CNES).

The tagline for the Orfeo Toolbox project is “Orfeo Toolbox is not a black box.”

Reproducible network benchmarks

I just found out about coNCePTuaL, a project that promotes reproducible research in the context of performance measurements for high-speed computer networks. (The capitalized letters in the name stand for Network Correctness and Performance Testing Language.)

The project is located at http://conceptual.sourceforge.net/ and is described in the paper Reproducible network benchmarks with coNCePTuaL by Scott Pakin of Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Some of the highlights of coNCePTuaL:

- Performance tests (timed network-communication patterns) are described in a precise but English-like “executable pseudocode” designed for basic readability, even by someone not familiar with coNCePTuaL.

- Output files produced by coNCePTuaL-based performance tests include not only the measurements but the code describing the test itself and a detailed description of the experimental platform on which the code ran. This enables a third party to see exactly what was run, how it was run, and what the results were, all in one file.

- coNCePTuaL can automatically produce space-time diagrams of the communication pattern for additional clarity of presentation.

Science in the open

See Greg Wilson’s post this evening Science in the Open for two stories of reproducible research.

A proposal for an Sweave service

Sweave has been discussed here many times, but here’s a brief description for those just joining the discussion. Sweave is a tool for embedding R code inside LaTeX files, analogous to the way web development languages such as PHP or GCI embed scripting code in HTML. When you compile an Sweave file, the R code executes and the results (and optionally the source code) are inserted into the LaTeX output.

Sweave has the potential to make statistical analyses more reproducible. But I doubt many realize its vulnerabilities. The Sweave files are likely to have implicit dependencies on R session state or data located outside the file. You don’t really know that the output is reproducible until it’s compiled by someone else in a fresh environment.

My proposal is a service that lets you submit an Sweave file and get back the resulting LaTeX and PDF output. An extension to this would allow users to also upload data files along with their Sweave file so not all data would have to be in the Sweave file itself. For good measure, there should be some checksums to certify just what input went into producing the output.

Here’s one way I see this being used. Suppose you’re about to put a project on the shelf for a while. For example, you’re about to submit a paper to a journal.You may need to come back and make changes six months later. You think about the difficulty you’ve had in the past with these sorts of edits and want to make sure it doesn’t happen again. So you submit your Sweave document to the build server to verify that it is self-contained.

Here’s another scenario. Suppose you’ve asked someone whom you supervise to produce a report. Instead of letting them give you a PDF, you might insist they give you an Sweave file that you then run through the build service to make your own PDF. That way you can have the whole “but it works on my machine” discussion now rather than having it months later after the person who make the report has a new computer or a new job.

Reproducibility talk in Houston this afternoon

I just found out that Keith Baggerly will be speaking at Rice University this afternoon. His talk is entitled “Cell Lines, Microarrays, Drugs and Disease: Trying to Predict Response to Chemotherapy.” Here is part of the seminar announcement most relevant to reproducibility.

In this talk, we will describe how we have analyzed the data, and the implications of the ambiguities for the clinical findings. We will also describe methods for making such analyses more reproducible, so that progress can be made more steadily.

The talk will be at 4 PM in Keck Hall room 102.

Peer review

Michael Neilsen posted an excellent article this morning Three myths of scientific peer review. He points out that peer review has only become common in the last 40 or 50 years. Maybe a few years from now someone will write an article looking back at how reproducible research came to be de rigueur. No one questions whether peer review is a good thing, though many people have complaints about the current system and argue about ways to make it better. Maybe the same will be said for reproducible research some day.

Taking your code out for a walk

When I was in college, a friend of mine told me he liked to take his code out for a walk every now and then. By that he meant recompiling and running all of his programs. At the time I though that was unnecessary. If a program compiled and ran the last time you touched it, why shouldn’t it compile and run now? He simply said that I might be surprised.

Even when your source code isn’t changing, the environment around it is changing. When I was in college, computers didn’t have automatic weekly updates, but they changed often enough that taking your code out for a walk now and then made sense. Now it makes even more sense. See Jon Claerbout’s story along these lines.